Egypt and the Silk Road

Reviewed by: Wafaa Elhouseiny

Translated by: Zeinab Mohamed

Egypt and the Silk Road

preface

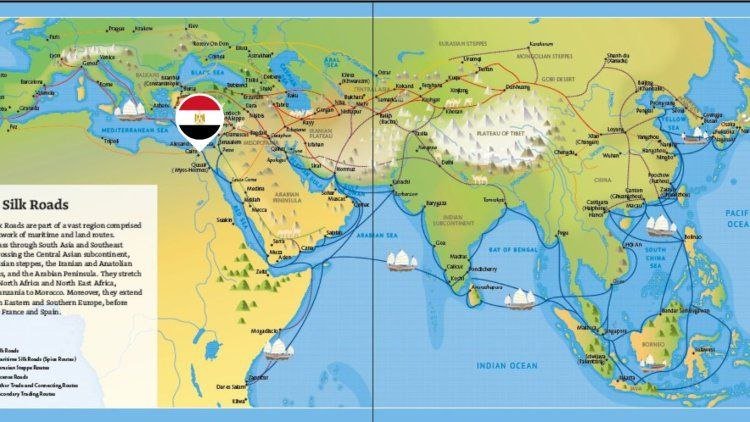

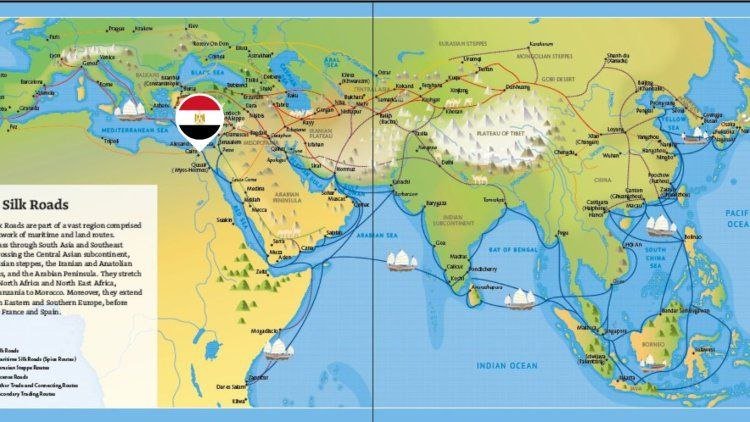

Since ancient times, humans have been accustomed to traveling from one place to another an establishing trade relations with their neighboring peoples, exchanging goods, skill, and ideas. Throughout history, transportation routes and trade routes were built in the Eurasian region, which were intertwined and interconnected over time to form what is known today as the Silk Roads. These are land and sea routes through which people from all over the world exchange silk and many other goods. The sea routes are considered a significant part of this network, as they represented a link connecting the East to the West by sea, and were used in particular for the spice trade so that their commo name became spice routes.

These vast networks not only carried valuable goods and commodities but also allowed the transmission of knowledge, ideas, cultures, and beliefs thanks to the continuous movement of peoples and their continuous mixing, which had a profound impact on the history of the peoples of the Eurasian region and their civilizations. It was not only trade that attracted travelers traveling along the Silk Roads, but rather the intellectual and cultural cross-fertilization that was also prevalent in the cities adjacent to these roads, to the point that many of these cities were transformed into centers of culture and learning. The communities living along these roads witnessed the exchange and spread of sciences, arts, and literature, not to mention handicrafts and technical tools. Languages, religions, and cultures soon flourished and intermingled.

The term Silk Road is actually a relatively new term, as these ancient roads did not bear a specific name throughout most of their ancient history. In the mid-nineteenth century, the German geologist, Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen, gave the name “De Seidenstrasse” (meaning the Silk Road in German) to this trade and transportation network. This name, also used in the plural form, still ignites the imagination with its suggestive mystery.

Silk production and trade

Silk is a fabric that came in ancient times from China, its original homeland. It consists of protein fibers produced by the silkworm when it spins its cocoon. According to Chinese beliefs, the silk industry began approximately in 2700 BC. Silk was considered a very valuable product, and the Chinese imperial court was unique in using it to make fabrics, curtains, banners, and other valuable textiles. The details of its production remained a secret that China strictly guarded for nearly 3,000 years thanks to imperial decrees that imposed the death penalty on anyone who dared to reveal the secret of silk production to a stranger. The graves of Hubei Province, dating back to the fourth and third centuries BC, contain beautiful examples of these silk textiles, including decorated fabrics, screens, embroidered silk, and the first silk garments in all their forms.

However, China's monopoly on silk production does not mean that this product was confined to the Chinese Empire without dispute. On the contrary, silk was used as a gift in diplomatic relations and its trade reached a great deal, starting with the regions directly bordering China and reaching remote regions, so that silk became one of China's main exports. During the Han Dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD). Chinese fabrics from this era have already been found in Egypt, northern Mongolia, and other locations around the world.

Sometime in the first century BC, silk entered the Roman Empire, where it was considered a luxury commodity, tempted by its exoticism, became extremely popular, and imperial decrees were issued to control its price. It remained in great demand throughout the Middle Ages, to the point that Byzantine laws were enacted to specify the details of weaving silk clothing, and this is the best evidence of its importance, as it was considered a purely royal fabric and an important source of income for the royal authority. In addition, the Byzantine Church needed huge numbers of silk garments and curtains. Hence, this luxury commodity represented one of the first catalysts for opening trade routes between Europe and the Far East.

Familiarity with the method of producing silk was extremely important, and despite the Chinese Emperor’s efforts to keep this secret well, the silk industry eventually crossed the borders of China and moved to India and Japan first, then the Persian Empire, and finally the West in the sixth century.

Expansion of roads and diversity of goods

Although the silk trade represented one of the first motivations for establishing trade routes across Central Asia, silk was only one of the many products that were transported between East and West, including textiles, spices, seeds, vegetables, fruits, animal skins, tools, wood and metal crafts, religious and artistic pieces, precious stones, and many others. The demand for the Silk Roads and the influx of travelers increased throughout the Middle Ages, and they remained in use until the nineteenth century, which attests not only to their feasibility but also to their flexibility and adaptation to the changing requirements of society as well. These trade routes were not limited to one line.

Merchants had many options of different routes penetrating various regions of Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia and the Far East, not to mention the sea routes where goods were transported from China and Southeast Asia via the Indian Sea towards Africa, India and the Near East.

These methods developed over time and with changing geopolitical contexts throughout history. For example, the merchants of the Roman Empire tried to avoid crossing the lands of the Parthians, enemies of Rome, and thus took the routes heading north through the Caucasus region and the Caspian Sea. Likewise, the network of rivers that crossed the steppes of Central Asia witnessed intense trade movement at the beginning of the Middle Ages, but its water levels would rise and then fall, and sometimes the water would dry up completely, and trade routes would change accordingly.

Maritime trade constituted another branch that was extremely important in this global trade network. Since the sea routes were especially famous for transporting spices, they were also known as the Spice Routes, and supplied markets around the world with cinnamon, allspice, ginger, cloves, and nutmeg, all coming from the Moluccas in Indonesia (also known as the Spice Islands), and a wide range of other goods. Textiles, woodworks, precious stones, metalwork, incense, construction wood, and saffron were products sold by merchants traveling on these roads extending over more than 15,000 kilometers, starting from the western coast of Japan, passing through the Chinese coast, toward Southeast Asia, India, all the way to the Middle East, and then to the Mediterranean Sea.

The history of these sea routes goes deep into the relations that existed thousands of years ago between the Arabian Peninsula, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley civilization. This network expanded at the beginning of the Middle Ages, as sailors from the Arabian Peninsula established new trade routes across the Arabian Sea and into the Indian Ocean. In fact, the Arabian Peninsula and China have been linked to maritime trade relations since the eighth century. Over time, long-distance sea travel became easier thanks to the technical achievements made in navigation, astronomy, and shipbuilding techniques combined. Lively coastal cities grew around the ports adjacent to these roads, which attracted large numbers of visitors, such as Zanzibar, Alexandria, Muscat, and Goa. These cities became rich centers for the exchange of goods, ideas, languages, and beliefs with major markets and crowds of merchants and sailors who were constantly changing.

In the late fifteenth century, the Portuguese explorer, Vasco da Gama, sailed around the Cape of Good Hope. He was the first to connect European sailors with sea routes passing from Southeast Asia, paving the way for Europeans to enter directly into this trade. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, these lucrative trade routes had become the subject of fierce competition between the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the British. Seizing the sea ports provided both wealth and security, because these ports were in fact dominating the sea trade lanes. It also allowed the authorities that exercised influence over them to declare their monopoly on this exotic commodity that was in high demand and collect the high taxes imposed on commercial vessels.

The map above depicts the huge variety of routes available to merchants who traveled carrying various types of goods, coming by land or sea from all over the world. Individual commercial caravans often traveled a certain distance along the road and then stopped to rest and stock up on supplies or to travel and sell their cargo in locations spread along the roads. This led to the emergence of commercial cities and ports full of life. The Silk Roads were characterized by vitality and were interspersed with ports and entrances. Goods were sold to the local residents living along it, and merchants used to add local products to their cargo. This process not only enriched the material profits of merchants and diversified the types of their goods, but also allowed the exchange of cultures, languages, and ideas along the Silk Roads.

Dialogue methods

Perhaps the most lasting legacy left by the Silk Roads is its role in bringing cultures and peoples together and facilitating exchanges between them. Traders on the ground were forced to learn the languages and traditions of the countries through which they traveled in order to successfully conduct their negotiations. Cultural interaction was a crucial aspect of material exchanges. Many travelers also dared to take these roads to enter into the process of intellectual and cultural exchange that was prevalent in the cities along these roads. These methods witnessed the exchange of scientific, artistic, and literary knowledge, as well as handicrafts and technical tools. Languages, religions, and cultures soon flourished and intermingled. Among the most prominent technical achievements that emerged from the Silk Roads to the world were paper-making technology and the development of printed press technology. The irrigation systems widespread in Central Asia also have characteristics that were popularized by travelers who not only brought their cultural knowledge but also absorbed the knowledge of the societies in which they landed.

The man usually credited with establishing the Silk Roads was General Zhang Qian, who opened the first road between China and the West in the second century BC. He was in fact on a diplomatic mission more than a commercial one. In 139 BC, Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty sent Zhang Qian to the West to make alliances against the Gyongnu people, who were historical enemies of the Chinese, but they captured and imprisoned him. He succeeded in escaping after thirteen years and was able to return to China. The Emperor was impressed by the abundance of details he provided and the accuracy of his reports, so he sent him on another mission in 119 BC to visit several peoples neighboring China. Thus, Zhang Qian paved the first roads extending from China to Central Asia.

Religion and the pursuit of knowledge were other motifs for traveling on these roads. Chinese Buddhist priests used to travel on pilgrimage to India to bring sacred texts. The diaries they wrote about their travels represent an amazing source of information. Not only do Xuan Zhang's memoirs (which span 25 years from 629 AD to 654 AD) have enormous historical value, but they also inspired a 16th-century comic novel, Pilgrimage to the West, which has become one of the greatest Chinese classics. European priests in the Middle Ages went to the East on diplomatic and religious missions, especially Giovanni da Pian del Carpini, sent by Pope Innocent IV on a mission to the Mongols from 1245 to 1247, and William of Rubruck, a Flemish Franciscan priest sent by the French King Louis IX to contact the Mangol tribes between 1253 and 1255. Perhaps the most famous of them is the Venetian explorer Marco Polo. He spent more than 20 years traveling between 1271 and 1292, and his account of his experiences became very popular in Europe after his death.

Roads also played an essential role in spreading religions in the Eurasian region. Buddhism is the best example of these religions that traveled on the Silk Roads, as artistic pieces. Buddhist shrines were found in sites as far apart as Bamyan in Afghanistan, Mount Wuyi in China, and Borobudur in Indonesia. Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, and Manichaeism spread in the same way, as travelers absorbed the cultures they encountered and brought them back to their homes. For example, Hinduism and then Islam entered Indonesia and Malaysia through Silk Road merchants who traveled the maritime trade routes of India and the Arabian Peninsula.

Traveling on the Silk oads

Travel along the Silk Roads developed with the development of roads themselves. In the Middle Ages, caravans drawn by horses or camels were the usual means of transporting goods by land. Caravanserais, which are large guest houses and lodges designed to receive traveling merchants, played a decisive role in facilitating the passage of people and goods on these roads. These inns, spread along the Silk Roads from Turkey to China, providing a constant opportunity for merchants to enjoy food, rest, and safely prepare for the continuation of their journey, and to exchange goods, trade in local markets, buy local products and meet other traveling merchants as well. This allowed them to exchange cultures, languages, and ideas.

As time passed, trade routes developed and their profits increased, thus increasing the need for caravanserais. The process of constructing them accelerated in various regions of Central Asia, starting from the tenth century until a late stage in the nineteenth century. This led to the emergence of a network of khans [Turkish word for the traveler's inn on the road] that extended from China to the Indian subcontinent, Iran, the Caucasus, Turkey, and even to North Africa, Russia, and Eastern Europe. Many of these khans still exist to this day.

Each khan was one day's walk from the next, an ideal distance to prevent merchants (and their valuable cargo in particular) from having to spend several days or nights in the open and be exposed to the dangers of the road. This resulted in, on average, the construction of a khan every 30 to 40 kilometers in well-served areas.

Sailor merchants faced multiple challenges during their long voyages. The development of navigation technology, especially knowledge of shipbuilding, enhanced the safety of sea voyages during the Middle Ages. Ports were established on the coasts intersected by these maritime trade routes, which provided vital opportunities for merchants to sell and unload their cargo and to supply fresh water. It’s worth mentioning that one of the major dangers that sailors faced in the Middle Ages was the shortage of drinking water. All commercial ships crossing the maritime Silk Roads were vulnerable to another danger of pirate attack because their expensive cargo made them desirable targets.

The legacy of the Silk Roads

In the 19th century, a new type of traveler frequented the Silk Roads. archaeologists, geographers, and enthusiastic explorers were seeking adventure. These researchers came from France, England, Germany, Russia, and Japan, and began crossing the Taklamakan Desert in western China, specifically in an area now known as Xinjiang. They intended to explore ancient archaeological sites spread along the Silk Roads, which led to the discovery of many antiquities and the preparation of many academic studies. Most importantly, it led to a revival of interest in the history of these roads.

Many historical buildings and monuments still stand to this day, marking the Silk Roads through caravanserais, ports and cities. However, the long and continuing legacy of this amazing network is evident in the many interconnected yet different cultures, languages, customs and religions that have grown along these roads over thousands of years. The passage of merchants and travelers of various nationalities not only generated commercial exchange, but also generated a large-scale process of continuous cultural interaction. Accordingly, the Silk Roads developed after their first exploratory journeys to become a driving force that urged the formation of various societies living in the Eurasian region and beyond.

New Silk Road

With the beginning of the 21st century, the importance of the Silk Road began to become apparent and flourish again. The international railway line was established on the ancient Silk Road, which begins from the city of Lianyungang in the east and ends in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, with a length of ten thousand and nine hundred kilometers. Trade between China and the countries of Central Asia achieved a larger scale of growth. In 2008, a letter of intent was signed in the Swiss city of Geneva to invest in reviving the ancient Silk Road and some land routes in the Eurasian region between 19 Asian and European countries, including China, Russia, Iran, and Turkey, which restored the spirit of the ancient Silk Road.

On September 7, 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping presented for the first time the initiative to build the Silk Road Economic Belt, during a speech he delivered at Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan. On October 3 of the same year, he also proposed building the Maritime Silk Road for the 21st century, during his speech before the Indonesian Parliament.

By 2014, China issued the strategic plan to build “One Belt, One Road.” By the end of the year, specifically on December 29, the Silk Road Fund was established with a capital of $40 billion. The Fund would provide support for infrastructure construction, resource development, and industrial cooperation in countries located on the land and sea Silk Road.

On March 28, 2015, The National Development and Reform Commission of China, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Commerce issued two documents jointly. They were called Aspirations and Actions on Promoting the Joint Construction of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. These two documents were the public blueprint for formally advancing the construction of “One Belt, One Road.” They also provided an explanation of the background, principles and general framework of the Chinese initiative, and fully defined the contents and mechanisms of the initiative.

On January 16, 2016, the official start of operation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which was proposed by China and includes 70 members, aims to provide loans for infrastructure projects in the Belt and Road countries, and operates with a capital of 100 billion US dollars.

On April 27, 2019, Chinese President Xi Jinping opened the New Silk Roads summit, which lasted for two days with the participation of representatives from 150 countries. It aimed to market the Belt and Road project, which is a Chinese initiative that was established on the ruins of the ancient Silk Road. It also aims to connect China with the world by investing billions of dollars in infrastructure along the Silk Road, which connects it to the European continent, making it the largest infrastructure project in the history of mankind. This includes building ports, roads, railways, and industrial zones.

The project covers 66 countries on three continents: Asia, Europe, and Africa, and is divided into three levels, including focal regions, expansion areas, and sub-regions. It includes two main branches: the land Silk Road Economic Belt and the maritime Maritime Silk Road.

The Maritime Silk Road extends from the Chinese coast through Singapore and India towards the Mediterranean Sea. The land branch of the initiative includes six corridors:

- The new Eurasian land bridge extending from western China to western Russia.

- The China-Mongolia-Russia corridor, which extends from northern China to eastern Russia.

- The China-Central Asia-West Asia corridor, which extends from western China to Turkey.

- The China-Indochina Peninsula corridor, which extends from southern China to Singapore.

- The China-Pakistan Corridor, which extends from southwestern China to Pakistan.

- The Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar corridor, which extends from southern China to India

The railway line connects China with Europe, connecting 62 Chinese cities to 51 European cities spread over 15 countries. In Indonesia, the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway is a model project within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative proposed by China, as this line connects the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, with the city of Bandung.

In the United Arab Emirates, the Chinese company Harbin Electric International is cooperating with the Saudi company ACWA Power within the Belt and Road Initiative in a joint project. This aims at building the Hassyan complex for energy production using clean coal technology in Dubai, to contribute significantly to reducing the cost of Electricity for local families.

The first Saudi-Chinese cooperation project within the Kingdom in the Belt and Road initiative is the factory project of the Chinese Pan Asia company for basic and transformational industries in the city of Jazan.

In Pakistan, Chinese companies built a series of infrastructure projects that included roads, railways, and energy production points, linking the southern coast of the country with the Chinese city of Kashgar (northwest). This project, which is called the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, also includes the construction of highways and hydroelectric dams, and the introduction of modifications on the Pakistani port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea.

In Africa, for example, a railway called the Silk Road connects the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, to Mombasa, which contains the country's most prominent port overlooking the Indian Ocean.

In Uganda, a modern fifty-kilometer road to the international airport was paved with Chinese money. Moreover, China sponsored the transformation of a small coastal city in Tanzania into a port that may become the largest port on the African continent.

About one hour's drive south of Algiers, there is a Chinese-French bilingual sign bearing the phrase "One Road, One Dream" on the Atlas Mountains, to announce a project along a 53 km long, lip section of the north-south highway in Algeria, which is being implemented by China National Construction Engineering Group Co.

China has been Africa's largest trading partner for many years. Within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative, the two sides redoubled their efforts to advance cooperation in various fields.

China aims to secure a faster and safer route through this sea route for its oil imports from the Middle East. The Luban Crafts

, which covers several fields and specializations such as automation, cloud computing, electronic information, mechanical maintenance, industrial robots, and thermal energy applications, has been established in the United Kingdom, Egypt, Cambodia, Portugal, Djibouti, Kenya, and other 20 countries an international vocational education system that guarantees high standards. Add to this complete vocational education, from preparatory to secondary levels, and applied bachelor’s level to postgraduate studies. In addition, it aims to expand the establishment of Chinese cultural center and institutes to spread and teach the Chinese language and culture in many countries of the world.

Egypt's role in the Belt and Road Initiative

Egypt is the first African country to sign the Belt and Road Agreement with China.

In April 2019, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi participated in the second summit of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in the Chinese capital, Beijing.

Mr. President’s participation in the summit came within the framework of the importance of the Belt and Road Initiative at the international level, and Egypt’s keenness to interact with it in light of the fact that Egypt is one of China’s pivotal partners in the initiative, in light of the strategic importance of the Suez Canal as one of the most important sea lanes for global trade, in addition to what national projects represent. The major projects being implemented in Egypt, such as the Suez Canal Corridor Economic Zone, are of importance within the framework of the initiative, in addition to the consistency of the initiative’s axes with many of the Egyptian development priorities and national plans in accordance with Egypt’s 2030 plan for sustainable development, as well as the comprehensive strategic partnership relations that bring together Egypt and China.

Within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative, China has contributed to many pioneering projects in Egyptian-Chinese cooperation.

In 2008, the Egyptian-Chinese Economic Cooperation Zone (TEDA) was established on an area of 7.3 square kilometers and was expanded by six square kilometers in 2016 under a cooperation agreement signed by the presidents of the two countries. It works to enhance economic and trade cooperation between China and Egypt and attracts investments in an expanded manner.

In 2015, the Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM) signed a deal to finance infrastructure projects worth $10 billion in Egypt, which included the energy sector, the expansion of the port of Alexandria, and the development of urban railways.

In 2015, the Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM) signed a deal to finance infrastructure projects worth $10 billion in Egypt, which included the energy sector, the expansion of the port of Alexandria, and the development of urban railways.

Since 2018, the Chinese group has been constructing the iconic tower, which reaches a height of 385.8 meters. It is one of 20 skyscrapers within the framework of the Central Business District project in the New Administrative Capital in Egypt.

China also contributed to the construction of the 10th of Ramadan City light railway line east of Cairo, the capital of Egypt.

Egypt is working on implementing the North-South Corridor (Cairo-Cape Town Road), which aims to increase the rates of intra-trade and investment flows, which contributes to strengthening the efforts of the countries of the continent to achieve sustainable development goals and raise the standard of living of African citizens. This is in addition to the navigational link project between Lake Victoria and the Mediterranean Sea, as one of the infrastructure projects listed among the priorities of the COMESA bloc, due to the multiple economic and commercial interests it achieves.

Egypt is working on implementing the North-South Corridor (Cairo-Cape Town Road), which aims to increase the rates of intra-trade and investment flows, which contributes to strengthening the efforts of the countries of the continent to achieve sustainable development goals and raise the standard of living of African citizens. This is in addition to the navigational link project between Lake Victoria and the Mediterranean Sea, as one of the infrastructure projects listed among the priorities of the COMESA bloc, due to the multiple economic and commercial interests it achieves.

The Belt and Road Initiative works to enhance joint cooperation and contribute to the development of all participating countries in a way that enhances the building of a community with a shared future for humanity.

Sources

UNESCO website.

World Bank website.

Website of the Presidency of the Arab Republic of Egypt.

Website of the Egyptian State Information Service.

Website of the Information, Support and Decision Center - Presidency of the Council of Ministers - Egypt.

China Network in Arabic.

Chinese People's Daily.